CUYO

The Cuyo region consists of the Andean provinces of Mendoza and San Juan, and adjacent San Luis. Settled from and once part of Chile, the area still retains a strong regional identity and its considerable mestizo population differs from the people of Buenos Aires and the Pampas.

The term “Cuyo” derives from the Huarpe Indian Cuyum, meaning “sandy earth”.

The formidable barrier of the Andes is the backdrop for the one of Argentina’s most important agricultural regions. This produces grapes and wine mostly for the internal market, rather than beef and grain for export.

Aconcagua, at 6960 meters the highest peak in the Americas, towers over the area. Cuyo lies in the rain shadow of the massive Andean crest, but enough snowfall accumulates on the eastern slopes to sustain the rivers which make the irrigation of extensive vineyards possible. Because of these advantages, Mendocinos, the inhabitants of the province of Mendoza, call their home La Tierra del Sol y del buen Vino (Land of Sun and Good Wine).

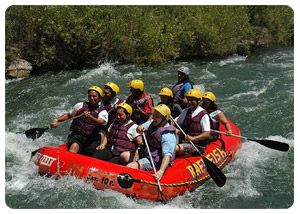

With its variety of terrain and climate, Cuyo offers outdoor recreation the year round. Possible summer activities include climbing, trekking, riding, hang-gliding, canoeing, fishing, water-skiing, windsurfing and sailing. In the winter, skiing is a popular if costly pastime. Most people visit Mendoza in traveling between Santiago de Chile (Chile) and Buenos Aires, but you should not overlook the others provinces, particularly San Juan, for off the beaten track experiences.

MENDOZA PROVINCE

Despite the physical barrier of the Andes, for most of its history Mendoza has been isolated from both the other Andean provinces and the distant Pampas. In large part this resulted from an accident of history, the settlement of Cuyo from Chile.

Like their counterparts in the Tucumán region, the Huarpe Indians of Cuyo practiced irrigated agriculture. Their population was large enough to encourage Spaniards to cross the 3850 meters Uspallata Pass from Santiago to establish encomiendas, but the impossibility of traversing the mountains during winter stimulated economic independence and encouraged political initiative. Still, trans- Andean communications were the rule, with links to Lima vía Santiago rather than northward to Tucumán and Bolivia. Buenos Aires was a remote backwater.

|

|

Vineyards first became important during the colonial period, but after Argentine independence the economy declined with the closing of traditional outlets for their produce. Only after the arrival of the railroad in 1884 did prosperity return, permitting the expansion of grape and olive cultivation, plus alfalfa for livestock. Provincial authorities promoted modernization of the irrigation system to assist the agricultural sector. Despite the centralization of water management, the vineyards remain relatively small, owner-operated enterprises, most not exceeding 50 hectares. Since 1913, the annual Fiesta de la Vendimia has celebrated the famous provincial wines.

Besides the towering Andean landscape and its popular-lined vineyards and orchards, the province offers several nature reserves and important thermal baths. It is a popular destination for both summer and winter holidays.

MENDOZA

Founded in 1561 and named for the governor of Chile, the provincial capital sits 761 meters above sea level in the valley of the Río Mendoza, east of the Andes. Earthquakes have often shaken the city, most recently in 1985.

Except during its long siesta hours, Mendoza is a lively city, its bustling down-town surrounded by tranquil neighborhoods where, every morning, meticulous shopkeepers and housekeepers swab the sidewalks with kerosene to keep them shining. The acequias (irrigation canals) along its tree lined streets are visible evidence of the city’s indigenous and colonial past, even where modern quake-proof construction has replaced fallen historic buildings.

With a population exceeding half a million, Mendoza is the most important administrative and commercial centre in the province. It has also an important state university and a growing industrial base, supported by nearby oilfields.

Orientation: Plaza Independencia occupies four square blocks in the centre of towns; on weekends there are often open-air concerts there. Two blocks from each of its corners, four smaller plazas are arranged in a virtual orbit. Beautifully tiled, recently restored Plaza España deserves particular attention for its Saturday morning artisan’s market.

Avenida San Martin, which crosses the city from north to south, has many sidewalk coffee houses. Briefly on weekdays but almost religiously on Saturdays, Mendocinos socialize here; is a good place to meet local people. The popular-lined Alameda, beginning at the 1700 block of Avenida San Martin, was a traditional place for promenades in the 19th century.

ARGENTINE WINE

In the dry, semi desert valleys and foothills of Mendoza, San Juan and San Rafael, the sun shines 300 days a year and pure mountain water from melting snow rushes down from the Andes, irrigating miles of land that produces 70% of Argentina’s wine. The province of Mendoza, by far the most important wine-producing region, lies at the foot of the Andes at southern latitudes similar to the northern latitudes of the best vineyards of France, Italy and California. With 300,000 acres of vineyards, Mendoza alone produces 65% of the nation’s wine. The rest comes from the northern provinces of Jujuy, Salta, Catamarca and La Rioja (where former President Menem´s family owns a winery), and the southern province of Río Negro.

|

|

Argentina, with its 1,500 wineries, is the fourth-largest wine producer in the world, yet its fine malbecs, syrahs, cabernets, chardonnays, and chenin blancs have seldom been seen on shelves or wine lists in other countries. One reason is that Argentines have been the primary consumers of all they produced – only the French and the Italians drink more wine per capita, so there hasn’t been much of a need to export. Secondly, cheap, hearty reds satisfied the beef-eating Argentines, and the white wines are sweet, which means that they haven’t done well elsewhere. In 1970, for instance, Peñaflor exported an economical cabernet under the Trapiche label; though it was good enough for Argentines, it was not equal to what California was producing and it didn’t impress American wine drinkers who were just beginning to consider California wines as an alternative to French or Italian vintages. Thirdly, collective marketing of Argentine wine (or collective anything) went against the grain in this land stubborn individualists.

|

|

In the early 90´s, wine consumption in Argentina declined, partly because people started drinking more beer. While Chile farmed cooperative marketing groups and aggressively sold their excellent wines in the United States and elsewhere, Argentines continued their individualistic approach to marketing.

When President Menem took over the government in 1989, the Argentine economy began to stabilize, and foreign investors took a new look at Argentina’s potential wine industry.

One vineyard that has been changing with the times is Bodegas Esmeralda, which in the 1970s was Argentina´s second larged wine producer. In 1974 Dr. Nicolas Catena, a Columbia educated economist and former professor at the University of California at Berkeley, whose family awns Bodegas Esmeralda, visited the Napa Valley and observed the high quality wine being producer there. Upon returning to Argentina, he decided to go for quality instead of quality. As a result, he and other Argentine vintners are now discovering a whole new market at home and abroad.

|

|

The bold, fruit-flavored Malbec grape came to Argentina from France as a blending grape, thrived in Mendoza’s soil and climate, and earned its right to be vinified as Argentina’s signature red wine. Although Chardonnays and Chenin blancs are being improved and adjusted for export, Torrontés seems destined to be Argentina’s signature white wine. Some of the region’s best vineyards are Bodegas Escorihuela, Bodega La Colina de Oro, Bodega La Rural and Villa Orfila, just outside of Mendoza; and Suter and Bodega Valentín Bianchi in San Rafael.

MENDOZA (Distance of Mendoza from other Argentine cities)

1,040 Km (250 mi) west of Buenos Aires, 340 Km (211 mi) northeast of Santiago, Chile, 1,381 Km (875 mi) north of Bariloche, 721 Km (448 mi) southeast of Córdoba, 609 Km (378 mi) south of la Rioja, 1308 Km (812 mi) south of Salta , 166 Km (103 mi) south of San juan, 264 Km (164 mi) west of san Luis, and 232 Km (144 mi) north of San Rafael in Mendoza.

Mendoza, the capital of the province of the same name and the main city in the Cuyo, prides itself on having more trees than peoples. The result is a town with cool, leafy canopies of poplars, elms, and sycamores over the streets, sidewalks, plazas, and low buildings. Water runs in canals along the streets, disappears at intersections, and then reappears in bursts of spray from the fountains in the city’s 74 parks and plazas. Many of these canals were built by the Incas long before 1561, when García Hurtado de Mnedoza, governor of Chile, commissioned Pedro Castillo to lead an expedition over the Andes with the purpose of founding a city and opening the way so that knowledge could be brought back of what lay beyond.

|

|

Argentina’s beloved hero, José de San Martín, resided here while preparing his army of 40,000-soldiers to cross the Andes in 1817 on the campaign to liberate Argentina from the Spaniards. In 1861, an earthquake destroyed the city, killing 11,000 people. The city of Mendoza and the Cuyo remained isolated from eastern Argentina until 1884, when the railroad to Buenos Aires was completed and the city was rebuilt. Immigrants from Italy, Spain, and France then moved here in search of good land to farm and grow grapes, and brought their skills and crafts to the region.

Avenida San Martín is the town’s major thoroughfare. Between it and the Plaza Independencia, Mendoza’s central square, are many shops, restaurants, and businesses-only street lined with shops and outdoor cafés. Maipú, Luján de Cuyo and Guaymallen are all suburbs of Mendoza with shopping centers, restaurants, and hotels. Take a taxi there; they’re cheap and more direct than local bus service.

The Parque General San Martín, about 10 blocks from the city center, is a grand public space with thousands of species of plants and trees, tropical flowers, and a rose garden. A race course, golf club, tennis courts, observatory, rowing club, and museums are some of the attractions in the park. In 1995, World Cup soccer was played in the nearby stadium. Atop Cerro de la Gloria (Glory Hill), in the center of the park, a monument depicts scenes of San Martin’s historic Andes passage.

PARQUE PROVINCIAL ACONCAGUA

390 Km (242 mi) roundtrip, northwest of Mendoza via R7

The Parque Provincial Aconcagua extends for 165,000 acres over wild, high country with few trails other than those by climbing expeditions up the impressive Cerro Aconcagua (Aconcagua Mountain). Organized tours on horse or foot can be arranged in Mendoza.

The drive up the Uspallata Pass to the Parque Provincial Aconcagua is a spectacular as the mountain itself. Tours can be arranged, but renting a car is well worth it as there are many sights to stop and photograph along the way. You can make the trip in one long, all-day drive or stay a night in route. Note that driving in winter on the ice roads can be treacherous and that you should be aware of the change in altitude from 2,500 ft in Mendoza to 10,446 ft at the top.

|

|

Leaving Mendoza early in the morning, head south on Av. San Martín to the Panamericana Highway (R7) and turn right. Green vineyards soon give way to barren hills and scrub brush, as you follow the river for 30 Km (19mi) to the Termas Cacheuta if you’re still engulfed in fog and drizzle, don’t despair: When you reach the Potrerillos Valley, 39 Km (24 mi) away, it’s likely that you’ll break through into brilliant sunshine. The road follows the fast flowing Río Mendoza and an abandoned railroad track that once crossed the Andes to Chile. In 1934 an ice dam broke and sent a flood of mud, rocks, and debris down the canyon, carrying off everything in its path. Evidence of this natural disaster is still visible all along the river.

At Uspallata, the last town before the Chilean frontier, excursions into the mountains by 4x4 or on horseback lead to abandoned mines, a desert ghost town, and spectacular mountain scenery where the movie Seven Days in Tibet was filmed. After passing Uspallata, the road goes through a wild, barren landscape of rolling hills and brooding black mountains. Along the way, the Río Blanco and Río Tambillos rush down from the mountains into the Río Mendoza, and remnants of Inca tambos (resting place) remind you that this was once an Inca route. At Punta Vacas, the corrals that once held herds of cattle on their way to Chile lie abandoned alongside now defunct railway tracks. Two Km (1 mi) beyond the army barracks and customs office, three wide valleys converge. Looking south, you can see the second highest mountain in the region, Cerro Tupungato (22,304 ft). The mountain is accessible from the town of the same name, 73 Km (45 mi) southwest of Mendoza.

|

|

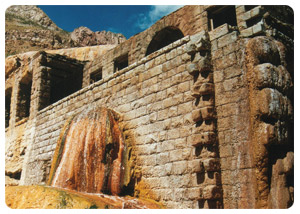

After passing the ski area at Los Penitentes (named for the rock formations on the southern horizon that resemble penitent monks), you arrive at Puente del Inca (9,000 ft), a natural bridge of red rocks, saturated and encrusted with yellow sulphur, spanning the river.Once a splendid hotel was here; but it, too, was a victim of the 1934 flood. A few miles farther west, after passing the customs check (for Chile), is the entrance to the park and a cabin where the park ranger lives. About 15 Km (9 mi) beyond the park entrance, the highway passes Las Cuevas, a settlement where the road forks right to a tunnel and the new road to Chile, or left to the statue of Cristo Redentor (Christ the Redeemer) on the Chilean border (13,800 ft), commemorating the peace pact of 1902 between the two countries.

|

|

The main attraction of the Parque Provincial Aconcagua is Cerro Aconcagua itself. At 22,825 ft, it’s the highest mountain in the world outside of Asia and it towers over the Andes, with its five gigantic glaciers gleaming in the sun. More than 400 expeditions have attempted the summit and Aconcagua has taken 37 fatal victims and dozen partially frozen. Nevertheless, every year hundreds of mountaineers arrive; ready to conquer the “giant of America”. A trail into the park begins at the ranger’s cabin and follows the Río Horcones past a lagoon and continues upward to the Plaza de Mulas base camp at 14,190 ft, where there’s a hotel.

SAN RAFAEL

240 Km (150 mi) south of Mendoza, 1,000 Km (620 mi) northwest of Buenos Aires.

A series of dams along the Río Atuel and the Río Diamante has created an agricultural oasis surrounding the second largest city in Mendoza Province. Cold winters, warm summers, and late frosts guarantee high-quality grapes for the area’s major vineyards, such as Suter and Valentín Bianchi, not to mention the many fines, smaller, family-owned operations such as Simonassi Lyon and Jean Rivier.

|

|

It’s easy to get around in the town. Two avenues, Hipólito Irigoyen and Bartolomé Mitre, meet head on in the center of town at the intersection with Avenida San martin. The siesta here is sacred and lasts from lunch until 04:30 PM, at which time shops reopen and people go back to work. Plenty of restaurants, sports stores, raft and kayak companies, and picnic spots along the river have swimming holes and raft launchings. The Hotel Valle Grande has it all; mountain biking, horseback riding, rafting, and kayaking.

MALARGÚE AND LAS LEÑAS

193 Km (120 mi) south of San Rafael via R 40

In the southwest part of Mendoza Province, the small town of Malargüe was a populated by the Pehunche until the Spanish arrived in 1551, followed by ranchers, miners, and petroleum companies. In 1981, an airport was built to accommodate skiers headed for the nearby Las Leñas ski area, and since then Malargüe has made earnest strides toward becoming a year round adventure tourism center.

|

|

The Las Leñas ski area, 430 Km (600 mi) west of Buenos Aires by air, 70 Km (43 mi) from Malargüe, 445 Km (276 mi) south Mendoza (7 hrs by car or less by charter plane), and 200 Km (124 mi) south of San Rafael, is the biggest and the highest ski area in Argentina. In fact, with a lift capacity of 9,200 skiers per hour, Las Leñas is the largest ski area served by lifts in the western hemisphere bigger than Whistler/Blacomb in British Columbia, and Vail and Snowbird combined. From the top, at 11,250 ft, a treeless lunar landscape of lonely white peaks extends in every direction. Numerous long runs (the longest is a 8 Km (5 mi) drop, 4,000 ft) extend over the 10,000 acres of ski able terrain. There are step, scary, 2,000 ft vertical chutes for experts, machine-packed routes for beginners, and plenty of intermediate terrain in between.

|